In conversation

Creation Stories

Simon Denny & Karamia Müller

Part one

Dome gallery

Simon Denny Creation Stories is both a project of research but also contextualisation and production. Kara and I have produced five diagrammatic sculptures that are made out of cable harnesses, made out of wire. We’ve also brought together a number of artworks by other artists that we think resonate with the themes of the exhibition and our conversation in general, which started with talking about family.

This show is about the value of connection—trying to understand what that can mean through all sorts of different lenses. Our conversation started when I met Kara five or six years ago through a mutual friend. We started talking about her surname, Müller. I live in Germany but grew up in New Zealand, and it was curious to me that there would be somebody called Müller living in Auckland. It’s a very normal, very common name in Germany, but not such a common name here. We started talking about her background and our mutual interest in technology. I had just started researching cryptocurrency and my practice up until that point had been looking into the stories that people who make technology tell us about the world; the stories that get presented to us by people who make things that have to do with the internet. It turned out that Kara was also interested in technologies and how those things affect people. We realised more and more that there was a dialogue to be had.

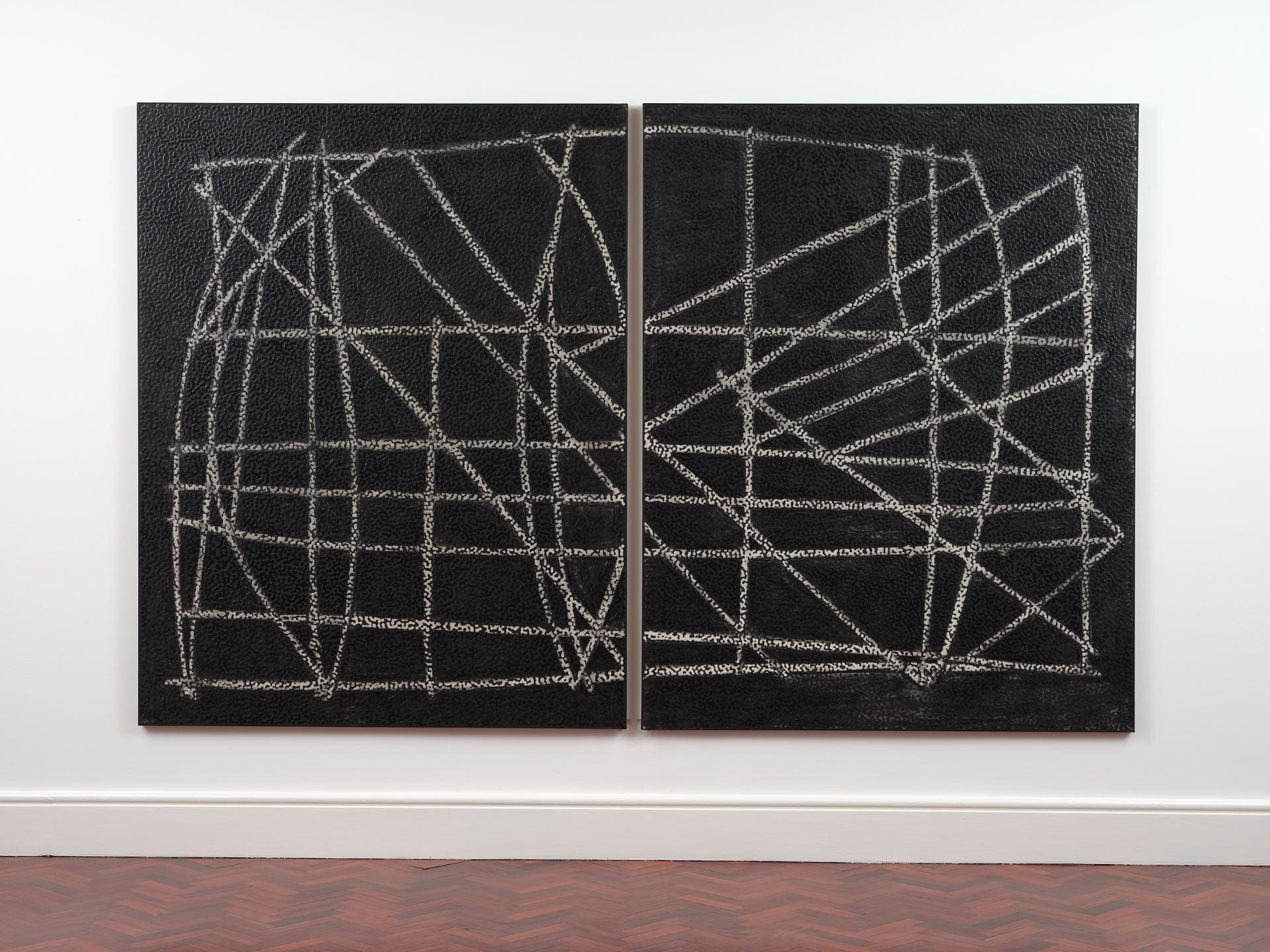

Creation Story Cable Harness 3 is something that is very close in format to producing machines. When you make a car or an aeroplane, for example, there’s a stage in the production process which involves bringing together all of the electrical cabling that will go into these machines. This is assembled on boards that look very much like this, often with a graphic diagram that the cables then get laid over the top of. That is called a cable harness. We first came across cable harnesses because we also started talking not just about Germany but Sāmoa, which both of us have familial connections to. My great-grandfather was in the legal world and was very briefly in 1921 the Chief Justice of Sāmoa, right at the beginning of New Zealand’s occupation after it had been occupied by Germans for a couple of decades. We then started to think about that in our conversations and we started mapping connections. We started making these maps of relation—both of our family histories and of significant other types of histories we thought resonated with those stories. We looked at a lot of commercial histories, we looked at technological histories, and we looked at biological histories. We came up with large diagrammatic social graphs which we thought would interestingly translate into some kind of format. When we were researching Sāmoa, we came across the fact that one of the most visible industries in Sāmoa is actually cable harness production. From the early 1990s onwards there has been a significant cable harness factory in Apia. We saw images of people working on these things and we thought this is kind of like a sculptural diagram.

Karamia Müller When we first started talking Simon brought up the idea of the supra-individual, which is a sociological term to talk about the things that impact and influence an individual. Simon is known for doing technological portraiture, portraits of key technologists, and I have figures in my family that I was interested in undertaking a kind of diagrammatic portraiture exercise. I’m particularly interested in the colonial history of Sāmoa, and we were also encountering this history of state to commercialisation and back again, this kind of movement of power across private to public spheres.

Central to Creation Story Cable Harness 3 was the tri-dominion, which was a rule of Sāmoa by the UK, the US and Germany. A particularly difficult time in terms of colonial rule because Sāmoans were very reluctant to make colonialism tidy by the settler colonists. At the time they saw it as a way of establishing peace and protect against civil war because of the competing interest which was disrupting some of the more traditional structures of power, and the political stability of the country. The way we thought through the state as an influencer of the supra-individual, how they’re created out of state power, and Sāmoa’s sovereignty influenced this board.

SD We can point out various different moments in this board. There’s five or six sections. Four large, ballooning forms come out of the centre, which is covering various moments in the British occupation of Sāmoa or the American attempt to occupy Sāmoa, the continuation of the New Zealand occupation and also the German attempt. Alongside those, various offshoots come out. Here we have, in this green and brown section, a map of various different plants that were encountered by colonists and catalogued. Here we have a little story of cable harnessing as kind of oppression between Sāmoa and New Zealand. I like to think of these as the veins of a machine that doesn’t exist. Like a speculative machine that is designed by these histories and stories interlinking.

When cable harnesses are made in the factories, they’re not finished machines. They’re to be put into another machine that will then work using their channels of connection. We worked with a couple of different formats. Some boards are like this, they don’t do anything. A couple of other boards are mining cryptocurrency, mining Ethereum, which is the second largest cryptocurrency after Bitcoin. It’s also the main cryptocurrency used for NFTs and other kinds of cryptoart. And there’s some familial and research connections that we’ll get to when we approach those boards.

From this board, we could speak to some of the other objects in the room. I guess the most prominent in the room is this beautiful painting Putahi Incandescent by Buck Nin, which has a resonance formally for me with these linear depictions of interconnection. Kara, as you introduced this painting, maybe you can speak about how we’ve spoken about it?

KM The inclusion of Buck Nin began at the very beginning of our curatorial creation story. One of the things we’ve talked about has been thinking through difference in productive terms or ways. Simon had just finished doing Mine at the Museum of Old and New Art in Tasmania and I was very interested in the ways that he was thinking about the metaphor of mining, both across technologies as well as foregrounding prevalent attitudes to the earth. As a way of countering that, I thought of the practice of Buck Nin. Buck Nin was introduced to me by Professor Deirdre Brown, who’s a Māori architectural historian, and the way I encountered Putahi Incandescent was framed as a section through the earth. The sectional view in the architectural context is a way of opening something up so that you can look inside. The fact this painting opens up the earth and what you encounter are living entities to me seemed like an interesting partner conversation to Simon’s work with Mine.

Stylised buildings are featured in Buck Nin’s representations under the earth. There’s multiple ways of reading that, but for me that’s a way of reading how the ancestral is embedded in the earth so closely so as to connect us ancestrally. I thought that that was a great counterpoint to what was being focused in on by the nature of inquiry in Simon’s own work. To bring that counter perspective view and foreground it as an exhibition experience in this context seemed appropriate to both of us.

There is another layer that we are considering throughout the exhibition, which is arts education and its relationship to the primitive object. Buck Nin was a pioneer in terms of arts education and for contemporary Māori practice. It’s this layering of meaning that makes this decision so interesting to us.

SD Maybe along those lines, it’s a useful moment to underline the fact that this show here is actually half of our Creation Stories activity. The other half is up the road at Michael Lett Gallery, which explores, maybe even more explicitly, the educational narrative. There are a number of works there that deal with New Zealand arts education, which I think resonate a lot with these conversations. There’s a key work by Michael Stevenson, made in the year 2000, called Genealogy, which were speculative School Certificate submissions as they may have looked by then well-known artists. They’re very convincingly rendered. The one that we have up at Michael Lett Gallery is one that he did after the work of Julian Dashper. It’s really amazing to see Stevenson’s speculation on what Dashper’s boards might have been. You see this weird appropriation of different cultural symbols, but also weird misinterpretations of art history. You see, for example, a drum kit that is also then suddenly Duchamp’s chocolate box, which, for those of you who know Julian’s work, is quite funny. The drums also represent another kind of play on creation stories, The Big Bang Theory, which was the series he did with artist names and drum skins.

Also up at Michael Lett Gallery is not only this fake art board, but also some real School Certificate art boards that I made when I was a teenager. Some very strange paintings that I produced during my education, kind of mapping what I was told art was. It interestingly resonates with other works in the show that were produced in various educational contexts, such as the work by Kara’s family. Family is important to these diagrammatic works, but also the themes of the show.

There’s a lot of familial content at Michael Lett Gallery. There’s also some work by my father, John Denny, who worked with Julian Dashper, producing a lot of his printed material. So there are these really interesting intergenerational conversations about producing knowledge and value.

Maybe that’s a good point to move to another work: Salle Tamatoa’s beautiful weaving and wood piece.

KM This work that we’re looking at here is representative of an intergenerational form of knowledge that’s being passed down from grandmother, Tunaga Funaki, to her grandson Salle. These are Salle’s innovation of the Niuean practice of weaving. Typically, it’s flat, it’s soft furnishing, and it uses raffia. Salle has since revisited the practice and innovated it using novel techniques. It’s typically gendered, but he’s included carving, which as a practice has its own relationship to telling Polynesian stories and translating an embodied intergenerational knowledge. This particular work is very special in that we were lucky enough to share some time with Tunaga and she told us how she considers the weaving as a sacred act of passing down particular practices that are specific to family. She taught Salle thinking that he’d continue the practice traditionally, but he’s gone on to create what’s is in their context and in their culture something that’s quite radical.

When they started to take up exhibition opportunities and first showed last year at Objectspace, she was concerned the community may not readily approve these innovations. In fact, they were quite celebratory and positive. I guess this idea or the notion of the creative practitioner, the indigenous and the passing across of skill sets, and what’s considered innovation and technologist in nature, is a something that resonates within the overall discursive space of this exhibition.

SD I think these questions were at the very centre of our conversation. What is technology and who gets to claim it? What is technological and what is innovation? Something I like about the many works of Salle and Tunaga that are in the show is how they situate some of the conversation around craft, art, and value in the foreground as well. I think they also help the cable harness works read as weavings in a way, which is a really interesting lens to see them through alongside the intergenerational and knowledge production part of that practice.

Another familial work of a completely different kind is sitting on this Mac desktop. It’s a software work by the American artist Ryan Kuo. There are many different types of practice that we wanted to put in the show. Some, like this one, are explicitly tech art. This is a program called Family Maker, where you open up different windows and it runs a word-based play of roles and conflicts within family situations. Every time you open up a new window, you have to make a decision that then brings in a different piece of an emergent familial picture. Interestingly enough, I managed to collect a copy of Family Maker, which Ryan sold as an NFT. So there’s also this very new dispersion and collection method in the background of the show as well.

Behind that is a work by D Harding titled Digging Stick, which is also explicitly a rendering of a tool. One of the things I think a lot about when I think about the stories that technologists tell us is how they often try and frame devices, computers, and the internet as tools. It’s a very strong narrative that is often foregrounded. Some say that this serves to depoliticise the object, and I think this kind of shovel/tool/painting artwork resonates a lot with those ideas as well.

KM The blue also references Ricketts’s blue, which was an innovation of painting that was born out of a colonial soap. Just the presence of that history and perhaps the questions that those histories raise within the conversational space of this exhibition is a focus for us.

SD Absolutely.

Maybe I should say something about the shelving unit that the cable harnesses are placed on. These works were produced by us, but also by a team of people in a lot of different roles. We had a lot of amazing help from a research assistant at the University of Auckland, Oliver Ray-Chaudhuri, and also a designer by the name of David Bennewith, who I’ve worked with for a number of years. David was born here, was also educated at the University of Auckland and now heads up the design department at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. David is most known for research that he compiled on the font designer Joseph Churchward, who is also a cousin of Kara’s. So again, there is a familial connection. All of the type layout was done by David in Joseph Churchward fonts. Joseph Churchward was probably the most prominent Sāmoan type designer. We also have a number of things from Joseph’s archive in the adjacent gallery to look at, including some currency designs he made.

The shelving is taken from the factory that the cable harnesses were actually produced at and in dialogue with; a place at Ardmore Airport called Swatek. Nick leads a team who build cable harnesses for all sorts of crazy machines and they took on our weird diagrammatic poetry on the side. When we were at Swatek, Nick hung one of these things up on a shelving unit that was just holding a bunch of wires. We were like, “Wow! That’s really quite an amazing thing.” We wanted to bring those in, so that’s why they’re on these old metal shelves.

On the back of this shelving unit, attached with little magnets, is the diagrammatic work of the academic Anne E. Guernsey Allen.

KM You’re probably getting a sense that it was very incremental the way these discussions have occurred and the way these boards have come about. One of the aspects that I brought to the conversation was the idea of documenting or developing languages that map the intangible. Anne E. Guernsey Allen is an anthropologist who undertook a study of traditional building in Sāmoa in the 1980s, around the time we were born. In that time, she set up an experiment that unfolded and was then refined, this idea that she could bracket and diagram space and the differences between Western building and traditional building of the Sāmoan fale. By bracketing and creating two different diagrams, she could, in that difference, see or create insights about the building process, in particular the ceremonial and the social. I see our own conversation operating in a similar way, that our two practices or key interests could come together, and in the difference gain insights around the way sociality is diagrammed. That’s also been part of the production of our diagrams here.

SD There is a colour-coding to the weaving on the cable harnesses. The brown and green definitely have to do with plants, but also, some of the national colours are used to denote these different sections as well. The German section is done in red, yellow, and black (the colours of the German flag) and various different blue, white and red ones are done for the British, the American and the New Zealand sections. Some of these things are very literal like that, and some are more associative. We also have this giant white cross with a black and multicoloured underlining, which is not particularly any sort of colour. We thought that was an interesting way to have a main vein of Sāmoa in there that wasn’t explicitly tied to these political histories. So it’s a selective history, it’s not a definitive history. It’s very much about mapping things that we found important to our conversation and that we thought would be interesting as a weaving. But there’s a lot more focus on colonial figures than, for example, on Indigenous figures. That is one of the things that came out from this particular diagram.

Part two

Gallery One

SD In this space, there’s a couple more of our cable harnesses and you’ll notice that there are these fans running on them. These are, as I mentioned before, actively mining Ethereum. Maybe it’s worth saying something about Ethereum and cryptocurrencies in general, and their relevance to the show and to these works. As I mentioned, the conversation started with our mutual family histories and putting them alongside various commercial histories. The first board there by the door, Creation Story Cable Harness 1, is mapping exactly those two stories. One thing that comes across on Kara’s side of the family is the fact that a cousin of hers, who lives in Zug, Switzerland where her great-great grandfather was also from, is a very important lawyer in the cryptocurrency world. He was responsible for designing the legal structure for the launch of Ethereum as a cryptocurrency. He had a hugely important role in creating this type of value in the world, the value of a new private currency.

KM There are multiple beginning points, but the genealogical is particularly central, which requires me to share a little bit of my background. I am Sāmoan and the way I’ve come to be Sāmoan is obviously a Sāmoan history, but the colonial side is Swiss. A Swiss sailor, who was not having much luck at the family mill in Zug and wasn’t having a lot of luck with the patriarchal way of splitting up inheritance, got on a boat and came down to the South Pacific. He ended up in Sāmoa where he fell sick. Once he fell sick, he was told by medical practitioners of the time, “You need to go to Tonga where it’s cooler. You really can’t take the humidity of this place.” So he lands in Tonga, he’s introduced to a Sāmoan woman, they marry and they start a copra plantation by leasing some land on an outlying island. Fast forward X amount of years and I’m here. But he was very close to his family, so he routinely wrote back telling them the conditions of his choice. We have those letters and we kept a family register, because my family are very interested in their own history. In those letters, he talks very much about how he wants to maintain the potential of opportunity for his offspring. So his offspring start the practice, probably embedded or entrenched in them, of sending their children back to Switzerland, in particular to Zug, for education.

In our family register, which is quite a complex document, it’s clear that when people go back to Switzerland and receive their education they struggle with making the decision whether to stay in Switzerland or to come back to the Pacific. Their hearts are obviously in the Pacific but they’ve also attempted some sort of social mobility in Switzerland, and the tension of them returning to Tonga is ever present in this dense family history.

A couple of lines do split off. One particular family member who was apparently the son who was meant to inherit the mill, marries and comes back to Tonga. He realises it’s not working out and returns to Zug. His progeny go on to become a central figure in our works, because his life has become one of quite different material circumstance to the family that have stayed in the Pacific—not myself, but my family in Tonga. For me, this kind of person seems to bring up really curious questions around how colonialism is embodied, how colonialism displaces and how colonialism is messy.

Whilst encountering the research that we were doing on my own familial line, I was reading Damon Salesa, a renowned Pacific historian. He talks about how the mixed-race body is one that seems to embody the colonial problem of not necessarily being able to establish a clean rule. These sorts of things seem to, in a way, start to turn over in the question of cryptocurrency. I was very interested that a family member who shares a great grandfather and whose inability to exist in clean ideas of the state resulted in a practice that brings crypto into state governance. I was very intrigued by this figure and he seemed to me like a supra-individual figure. Of course, I couldn’t help but talk to Simon about it and ask for his opinion, but also his expertise, to see whether or not these sculptural machines could potentially explore some of those ideas, which I was lucky enough they did.

SD Those lines of connection—the literal mapping out of those histories and interconnections between people, business, stories and geographies—are now literally running through those wires producing another kind of independent and private financial value. I think it’s such an interesting poetic thing. I mentioned the term before, the “social graph”. This is a term that I came across in the context of Facebook. As a platform, Facebook famously maps our interconnections as well. The objects that they produce financial value from are exactly these kinds of maps of relation called social graphs. When I was thinking about making these works, I was also thinking that we were producing a social graph of our own that produced another kind of financial value at the same time.

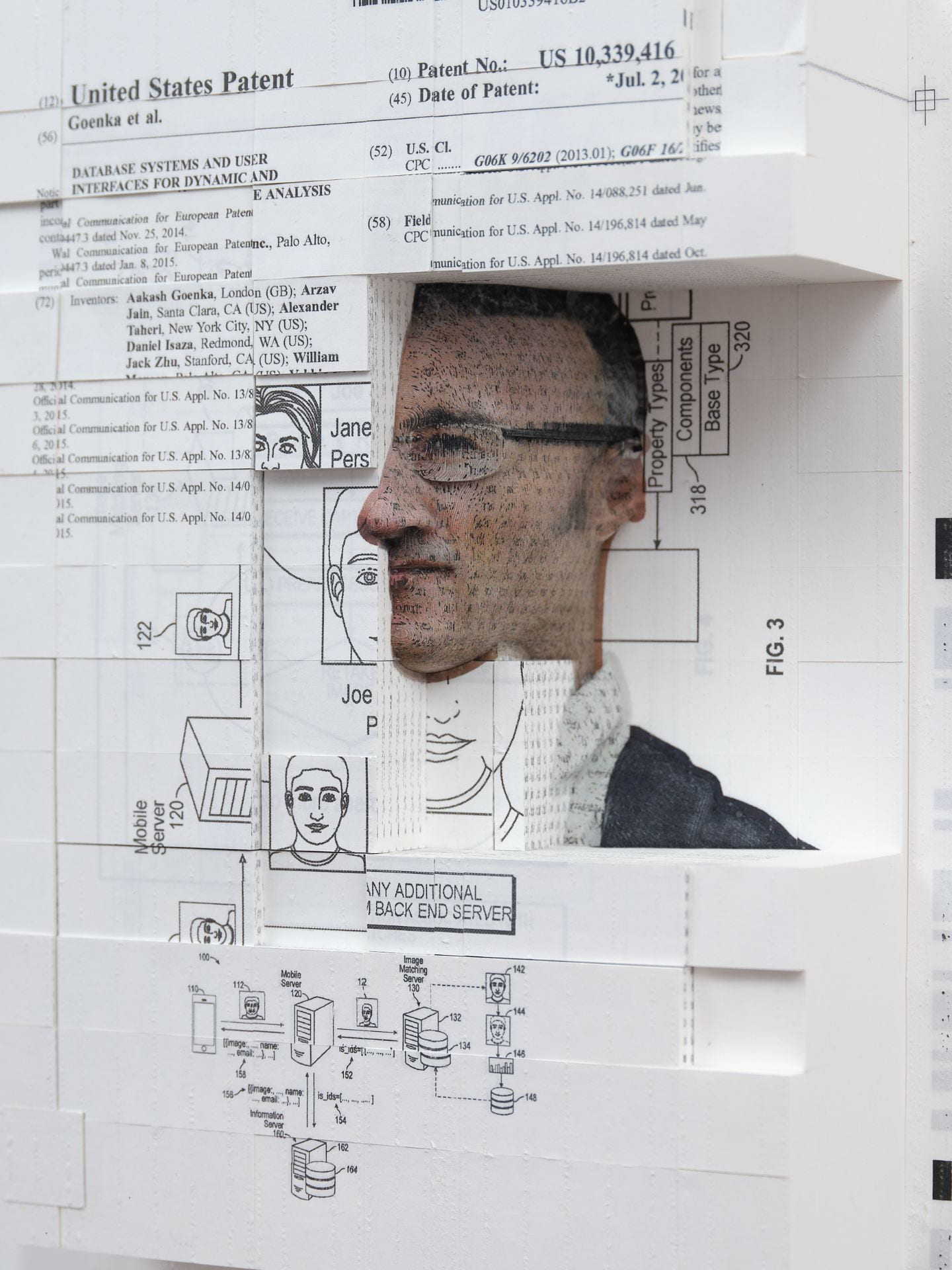

On that far wall just as you come in, there’s a tiny little work that I made last year titled Document Relief 29 (Palantir Image Identification patent). It’s a portrait of a founder of Palantir, another company that works with social graphs. Palantir basically produces social graphs (and many other kinds of data analytic packages) for states, governments and companies. There might be people in the room that use Palantir. It’s a very, very popular product. I made a portrait of one of the founders of that company out of a patent they have for facial recognition software. It’s a layering up of paper and a kind of carving of part of the face of Alex Karp, the founder. I thought that was interesting, not only because we were producing social graphs, but also as we started to think about this intergenerational knowledge production side as well.

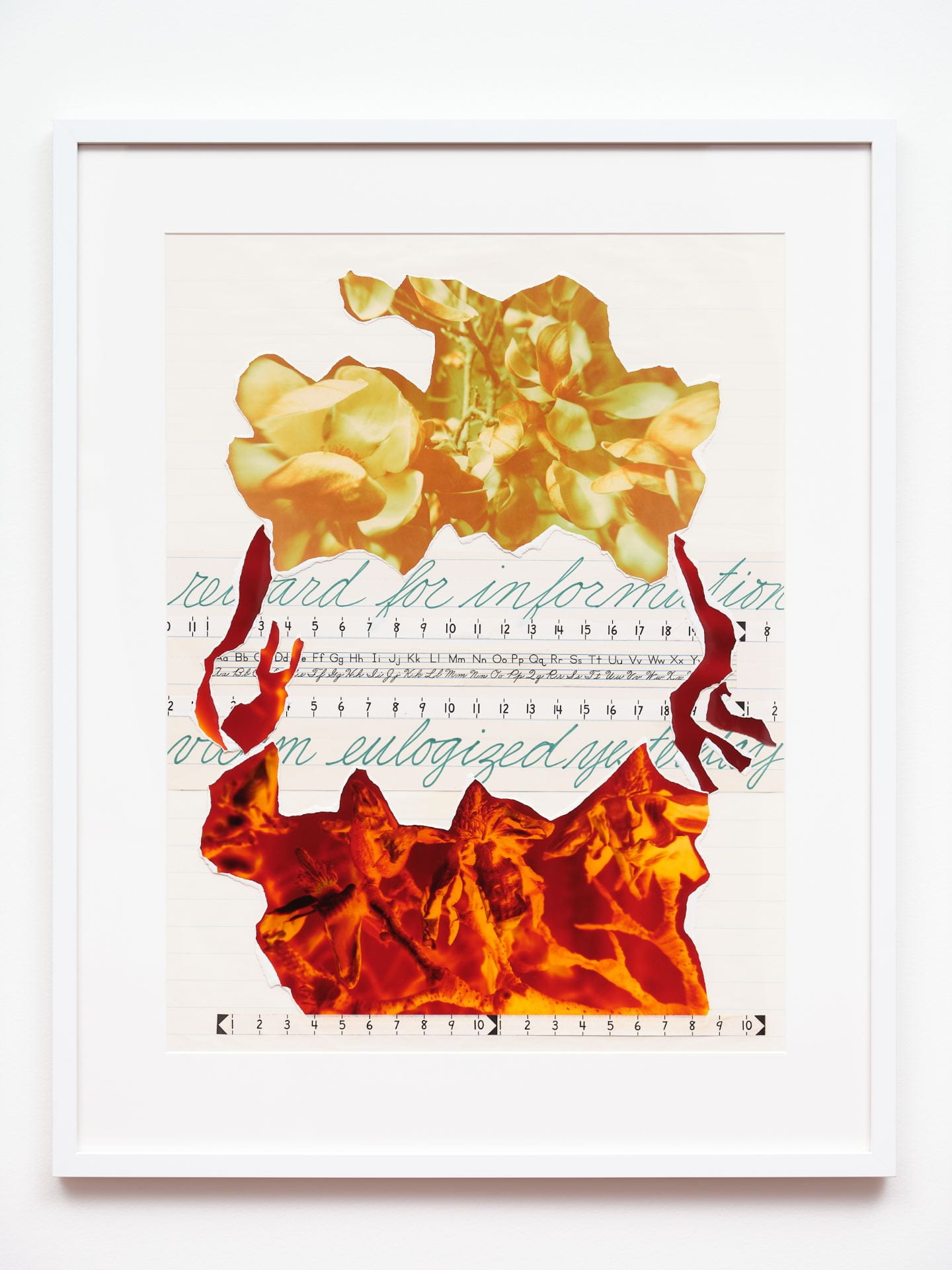

One of the people that came up in conversation was the work of Alex Karp’s mother, Leah Jaynes Karp, who was also an artist. Right there on the wall you have these beautiful purple, red and white collage pieces, which are by her. Those works are really interesting in many ways. They were produced in 1982 as a response to racialised killings that happened in Atlanta, Georgia. They play with some of the words that were spoken about the tragedy at the time. One very poignant title is Reward for Information-Victim Eulogized Yesterday. There’s also a work titled The Numbers are Growing. You can see in the botanical elements, drawings that are from learning how to write. I think all of these themes of intergenerational knowledge and the power of data are already present in the work of Alex Karp’s mother, before Palantir is even thought about.

KM Interestingly, as Simon brought up the software behind Palantir, critical to solving the crimes that these works reflect on was a piece of police surveillance. Simon has this incredible image of Alex Karp sitting under an image of Michel Foucault in his office and as we know there is this critical relationship between Foucault and the Panopticon and state surveillance more broadly—this layer of who is policed, who isn’t policed, and to what end? That aspect of difference also rhymes with some of the colonial question marks and the indigenous body within the exhibition.

SD Another special thank you to Lisa Beauchamp, Curator of Contemporary Art at Gus Fisher Gallery, and the supporters for working on this. This is the first time Leah Jaynes Karp’s works have been shown in New Zealand, and it may even be the first time they’ve ever been shown. They were accessioned into the collection of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta as part of a big package a couple of decades ago and I don’t think they were ever shown there. So it’s a really amazing thing that these works are on show.

Another thing to say about family history as it’s referenced in these diagrammatic pieces is from my own family history, and the relationship to value and money there. I mentioned that my great grandfather on my mother’s side was a judge who went to Sāmoa in 1921 and came back reportedly because it was too hot. He also had a couple of sons who stayed in the legal profession. My grandfather was a was a judge in Christchurch, but interestingly his brother, Gilbert Wilson, was the head of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in the 1950s and 1960s. He was overseeing the issuance of banknotes as New Zealand changed currency from pounds to dollars. So there’s this really interesting relationship to financial money production that is also in my family.

Something else in the room that rhymes with these objects is the largest work in the show, this beautiful painting by Daniel Boyd. Boyd’s work also has a resonance with my family history in some ways. Untitled (TI1) is a painting of a photograph of an object that was collected by Robert Louis Stevenson. Stevenson died in Sāmoa in the late 1800s and witnessed a lot of the conflicts that are depicted in Creation Stories Cable Harness 3. The object that the painting depicts is a Marshallese stick island navigation chart. So it’s a technology, a mnemonic tool for navigation, but it’s also a collected colonial object at the same time. For me there is a very literal rhyme with some of the forms of our boards as well.

KM Robert Louis Stevenson was also a very vocal critic of the colonial enterprise and he had an interesting relationship in that space. His house is now a museum. Its interior has become part of a national story of myth-making, and its relationship in time and space is that he used to sit there and watch the ships in the harbour. Those ships and their presence always had a sense of potential war. The relationship to militarisation and occupation is still kept in the exhibition’s conversational space.

SD Also, there are rumours or potential stories of my great grandfather having been in that house while he was Chief Justice.

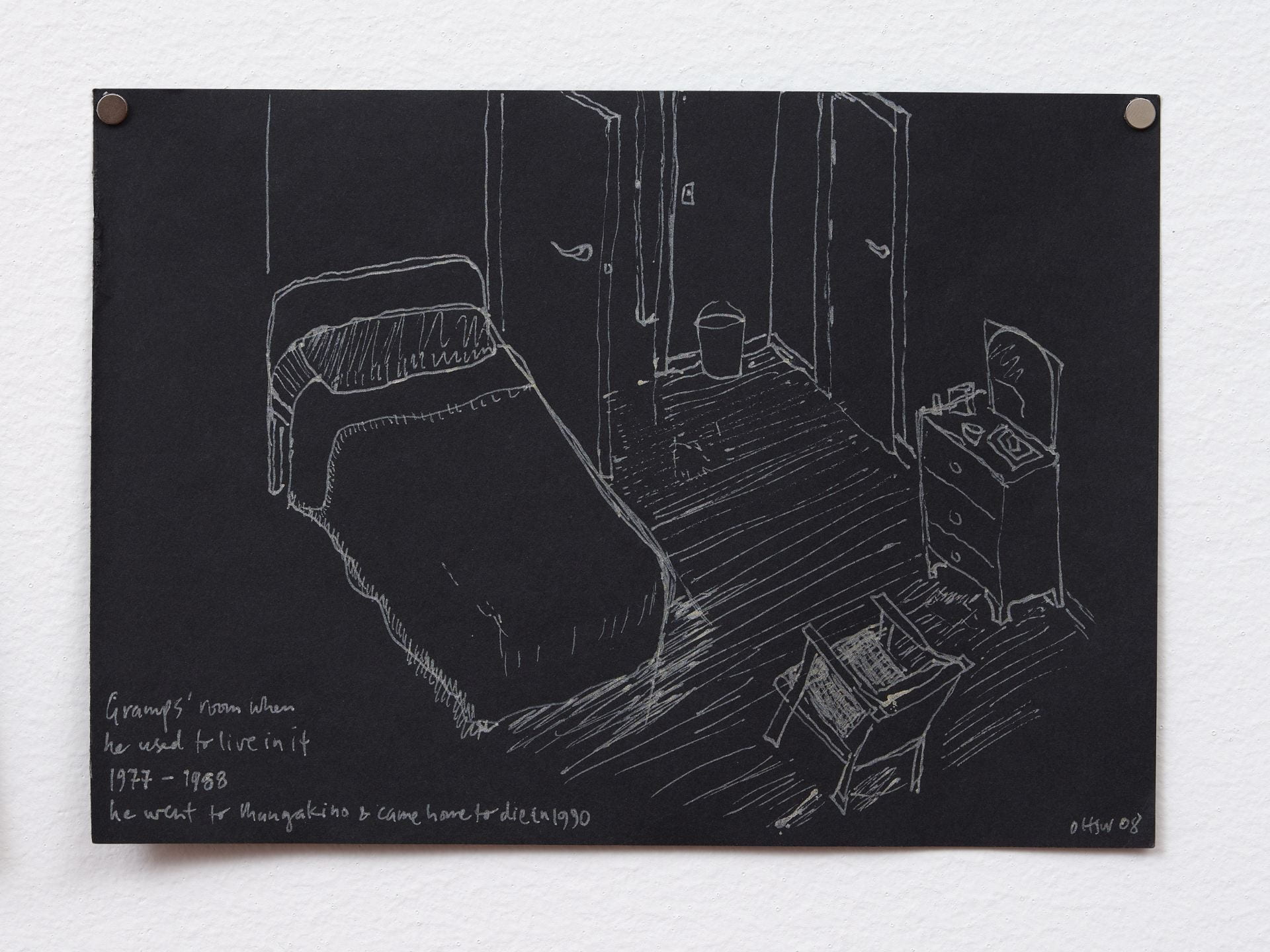

Another embodiment of domestic space and depiction of colonial history comes in these very small, beautiful drawings over there by Leafā Wilson and Olga Krause. They depict these spaces where she used to live and where she grew up, but also where family members died. There are these beautiful anecdotes and text about what those rooms are.

KM It’s probably a good time now to trek back and look to my own work, which started our conversation around technology. I’m an architectural researcher at the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of Auckland. One of my key concerns is thinking through how social events in Sāmoan culture and Sāmoan value systems critique or find the gaps in technology. For example, the way building software is programmed it’s not value-orientated towards capturing the value systems of cultures sitting outside Western ontologies. Leafā and Olga’s works rhyme in the sense that the space is made special because of what’s occurred there, the relationships that have occurred there, and the connectedness of those spaces. Having their presence here to speak to my own practice, as well as these other questions around the bodily, the embodied, and the intergenerational is thought provoking.

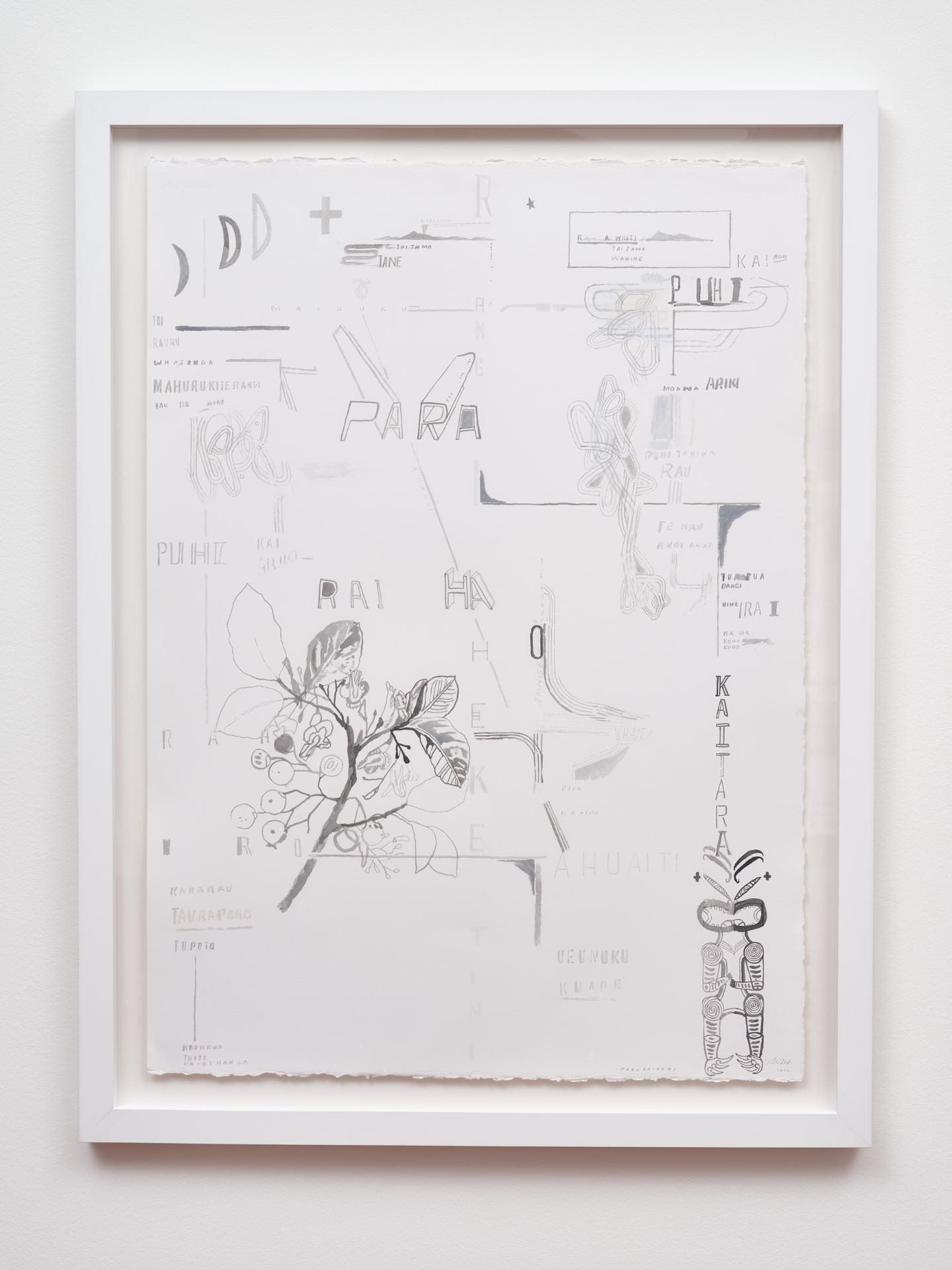

SD You can see Kara’s very beautiful drawings investigating exactly that question of what software can depict, and for whom, up at Michael Lett Gallery.

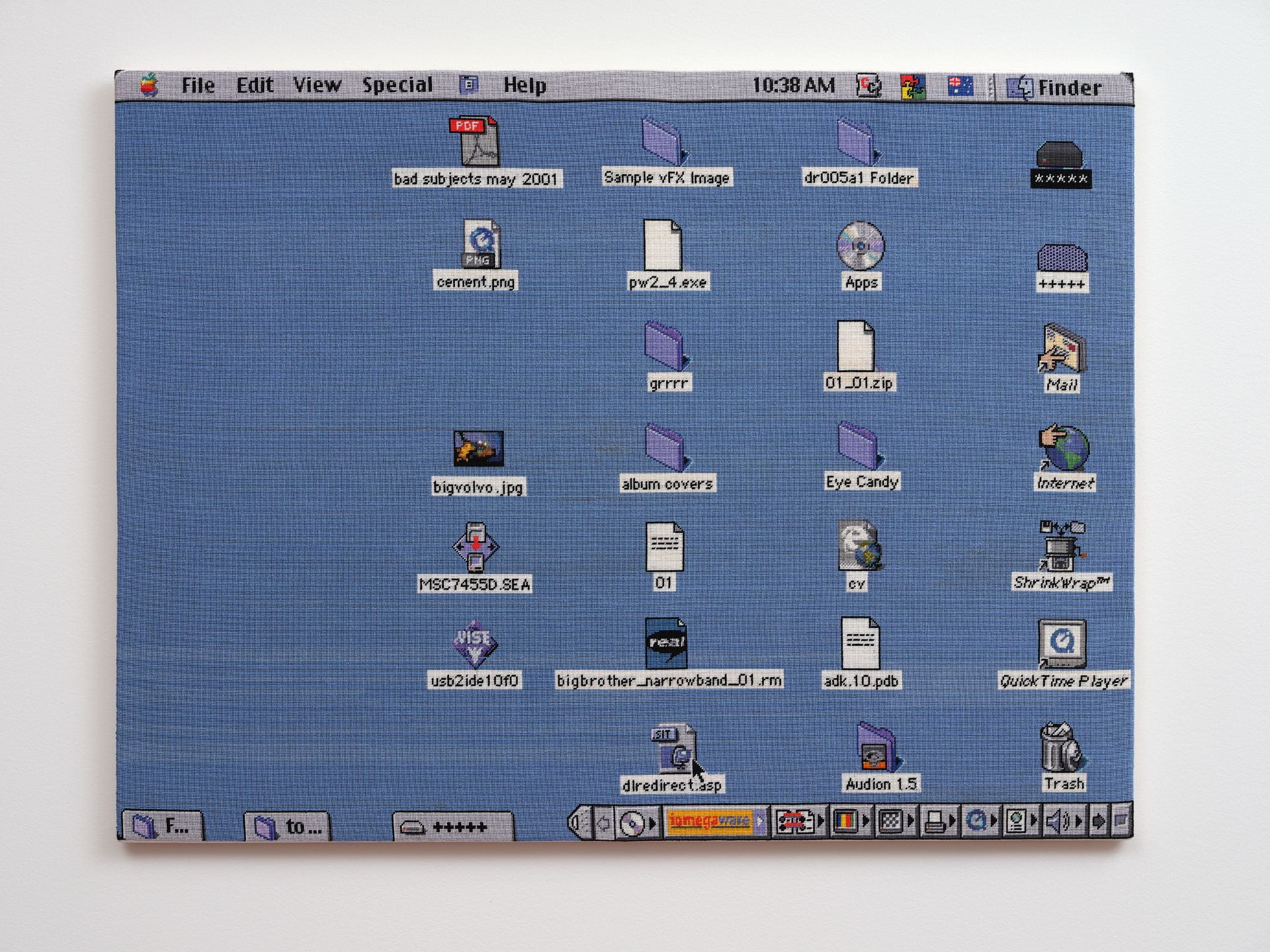

From a different type of domestic space, we have this work by Stella Brennan, borrowed from the Auckland Art Gallery collection. Tuesday, 3 July 2001, 10:38am is a beautiful, collectively-produced weaving that depicts a technological interface. Again, the weaving aspect comes in, the interface aspect comes in, and the collective aspect comes in through her work. It was produced over the course of a whole year between 2001 and 2002 from a screenshot of her Mac desktop. A really amazing piece there. That weaving is sitting next to another work of Salle’s that we spoke about earlier, this beautiful piece of wood with this winding cabling around it. It’s also very resonant.

One final work to speak about in the room is a very special work we borrowed from Shane Cotton, who was one of the first contemporary artists I ever became aware of, because his work was hanging at my high school. I looked at it every morning for about five years. He was also one of these people that we talked about in terms of education. He was one of the artist models whose work I very badly copied and reinterpreted. This is a piece that Shane made about his familial histories as well. It’s a special drawing that he produced for this show in dialogue with our questions about his own background.

There are many ways to read these cable harness works. One of the reasons why we contextualise the work alongside other types of weaving and diagramming, and other types of painterly imagery, is that for me, as a viewer, I like them to do many different things. On one level, it’s really just pattern-making. I like to follow the lines and the colours. On another level, of course, I like to get lost in some of the interconnections. I start with something that looks interesting, and then I follow along these different histories. I guess there’s no right way to read them. What we hope is that there are multiple ways to enjoy them—materially, diagrammatically, informationally, and aesthetically.

This text is adapted from a conversation between Simon Denny and Karamia Müller held at Gus Fisher Gallery on Saturday 6 August 2022 on the opening weekend of Creation Stories. The conversation took place between two galleries on site, the Dome Gallery and Gallery One.

Gus Fisher Gallery

74 Shortland Street

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Central 1010

Tuesday – Friday:

10am – 5pm

Saturdays:

10am – 4pm